|

|

The Sex Blog Of Record

November 24th, 2025 -- by Bacchus

Back in the 1970s, there was a genre of porn magazine that didn’t have a good name. Later, when magazine publishers were dumping random shareware programs onto CDs to sell with their computer magazines, the term “shovelware” was invented. But shovelware itself already existed in porn. Magazines with names like “275 Hot Cuties” and “300 Beautiful Babes” were all over the 1970s newsstands. They had very few, if any, color pages, and they achieved their high photo counts by including just a few full, half, and quarter-page pictures, with the rest of the count made up with baseball-card sized snapshots. There was little or no editorial text and never any model credits. This photo comes from one of these shovelware porn magazines:

I’ve always been a sucker for a winning porn smile, and this performer certainly has one!

Similar Sex Blogging:

November 22nd, 2025 -- by Bacchus

This video clip is from a Side+ branded gameshow from the UK, and that’s all I know about it. I don’t know if this hapless young man chose his partner for the game, or had any reason to trust her, but she does him dirty in the worst way:

Not only does she make no effort to minimize his electrical shocks, but at the end she smirks and jerks the wand against the machine repeatedly, just to watch him shriek and dance like an agonized organ-grinder’s monkey. Cruel!

Similar Sex Blogging:

November 20th, 2025 -- by Bacchus

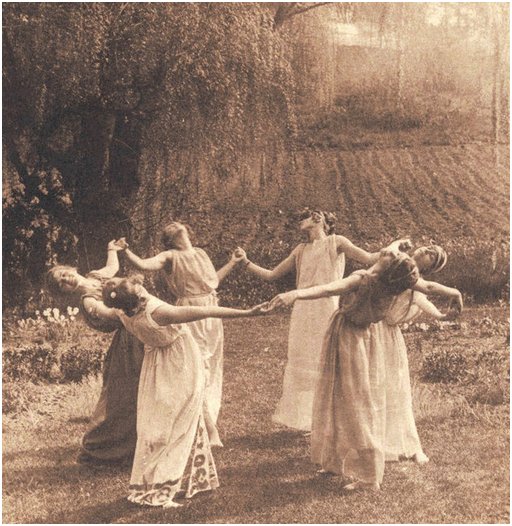

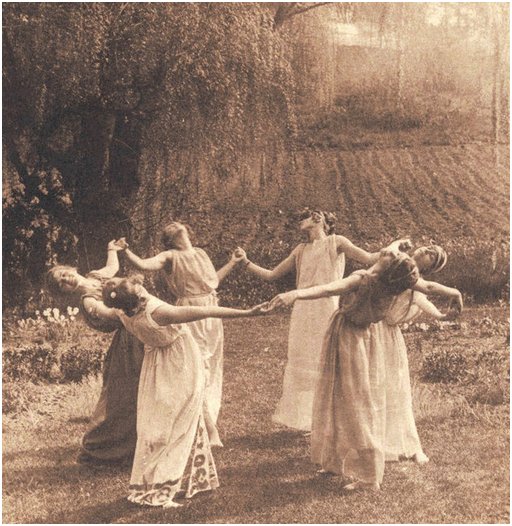

I don’t know precisely what ritual these six nubile witches are performing in this long-ago European-style garden, but usually when any six women join hands for ecstatic dance with bare feet on tightly-grazed lawns, the result regardless of intent is fertility and increase:

A number of sources, none of them authoritative, caption this photo “Vassar girls practicing their Greek dances, 1923”.

Similar Sex Blogging:

November 17th, 2025 -- by Bacchus

Jake in Australia talks about found porn, and what he did with it:

You know that one of the crowning achievements of my life was finding three bags of porn as I was walking home from school when I was 15. I was walking home in the rain from school in my Doc Martens. It was pouring rain, I’ve got my school bag on, I see a… just a garbage bag on the footpath. I kick it and porn magazines fly out of it. And then I found two other garbage bags right next to it, also filled with porn, and between the rain and that porn it felt like God was saying here, here’s something positive for you.

And it was so much porn, and it was raining so hard that I had nothing else to do! I needed to save these books. I needed them! So I took my school bag off and I emptied out the contents of everything. I threw away my textbooks. I threw away my maths book, like the actual the one for the year. Everything I had! My pencil case, even probably my graphics calculator, I just emptied out into the mud and water, and I just filled my bag to the brim with glorious glorious porno magazines.

So I had those for years. There was… there was heaps! So I used them, you know. And when I was about 18 or 19, it came time for me to get rid of them. I was getting rid of my desk, and all those magazines lived uderneath the desk. So I put them in the in the boot of my car which was a red VM Cavalier with a group 8 front grill. And I was driving around with it. I had them all in the boot and I was meant to throw them away, but I just never got around to it, so I just went around with a boot load full of porn everywhere.

Now I don’t know if you know this but at that time I couldn’t afford to really buy much petrol cause I was cheap. You know I… I just had no money. Um… So, I come up with this idea to just… to fill up my car with petrol and just drive away, every time I went to the petrol station.

So I used to do that all the time. One day after having done that, um, I’ve got, I’ve got a slab of beer, of Vic and I went down to around near my high school, around where Kialla was, and a bunch of chicks that I knew and a couple mates all sort of lived in that area there.

And I parked my car and um yeah, I was just sitting there, drinking in my car, listening to tunes cause there was part of that little section of Kialla that was still being built up, so there wasn’t many houses around, so you could turn up music and just drink there and talk shit, so that’s what we’re doing. Anyway, eventually we’re sitting there and I’m blind drunk and everyone is blind drunk, there’s like six or seven of us just standing around the car talking.

And the cops pull up and I’m drinking. I wasn’t driving, the car was parked, so the cops come up and they’re really suspicious. They’re like what are you doing? I said I’m drinking and he’s like well how did you get here? And I said oh my car’s broken, so we just walked down here with a slab and decided to listen to music. And so they couldn’t really say anything right?

And he kept asking the girls who were with are yous alright? Are yous alright here with him? And they were fine you know, we were just all we’re all old mates, and um, eventually the cop goes alright then I’ll let you go, just let me have a look around the car before I leave. Now I had the fake plates that I’ve been using when I was doing petrol runners, and quick sidebar: the plates that I had in there was stolen from Sacred Heart Church in Saint O’rourke’s, they belong to Father O’reilly, the priest. That’s who I took.

I figured I’d see like if any magic happened if I took em, like if good things had happened and fucking I’m telling you, when I finish this off you might think twice! So I had these plates, they were in the boot of my car and um he goes let me check your car. He popped the the bonnet, there was nothing illegal in there, just the shitty V6 engine. He pops the boot with… where the the illegal plates were, the stolen number plates, and I just hear him go, what the fuck is this?

And I said oh… and I had to come up with an idea that didn’t sound like I’ve been driving around with 10 tons of porn in the back that I found when I was fifteen. And he goes to me what is all this? And I said oh my uh, my grandfather owns a news agency and they went out of business and he told me to get rid of all this.

And he goes that’s great and he, the cop is sitting there looking through the porno mags. And he called his other mate over and he goes why, what are you doing with this, and I go mate we’re getting rid of it! I go you could use this for the station. Take it, take it all. And he goes I’m not taking it all! And I said no, well take a couple, all right mate?

Anyway he scooped up four or five of the favorites that he saw on there, and in the end he shut my boot with the stolen plates inside — didn’t notice them! — and just sat there just talking shit with us. Oh yeah, now I used to do what you boys… did you know… blah blah blah… you just look after each other… you’re a group there, you look after each other… and then him and his cop mate, they took off in the squad car and left us behind.

You can’t get a better outcome! You’re blessed, blessed. Blessed! The priest plates and that gift from God with all the porn, you just… the sun’s just shining on you! Sometimes the sun does shine on me.

Similar Sex Blogging:

November 15th, 2025 -- by Bacchus

Amazingly enough, versions of this Donald Trump and Bill Clinton blowjob joke have been circulating on Reddit and elsewhere for at least the last seven years:

So Donald Trump dies and he goes to hell. And when he gets there, he meets the devil, Mr. Satan himself.

And Satan says to him, listen, you’re definitely meant to be here, but we don’t have any room for you. So in order for us to accept you in, we’re gonna have to let somebody go. He says, but I’m gonna make it fair, and I’m gonna let you choose who gets to leave. So come with me.

So he takes Trump to three different doors, and he says, behind one of these doors is somebody you can set free and take their place. But like I said, I’m gonna let you make the decision.

So Donald Trump opens the first door and he sees Barack Obama, and he’s jumping off a diving board, landing in a pool, getting out of the pool, getting on the diving board and jumping back in. And he’s doing it over and over, repeatedly. And Trump goes, you know, I… I don’t think I can. You know, I don’t think I can do this for eternity. So, no, I don’t think I can do this.

Satan says, all right, we’ll check door number two. So he opens up door number two, and Richard Nixon is in there, and he’s got a hammer and he’s breaking rocks. And he just keeps breaking rocks, breaking rocks just consistently. Like, he breaks one rock, another rock appears. And Trump goes, you know, I got a bad shoulder. You know, golf injury, can’t be doing that either. So let’s go back to, uh… Let’s go check door number three.

So Satan takes him to door number three. And he opens the door and Bill Clinton is strapped to a bed. And Monica Lewinsky comes in and does what Monica Lewinsky was famous for doing, over and over and over again. Trump goes, no, yeah, I think I could… Yeah, I think I can handle this! I could get used to this. So, yeah, I’ll take door number three.

Satan smiles a big mile. Then he says all right, Monica! You’re free to go.

And… scene!

Image credits: Both images in this post were generated with the Perchance.org AI Image Generator. With due respect to people who think all uses of AI are unethical, I have been caught up in a lot of offline and private discussions on this topic in recent weeks and an emerging opinion that I am increasingly persuaded by has been that using AI to generate agitprop (highly politicized art) is fair game.

Similar Sex Blogging:

November 14th, 2025 -- by Bacchus

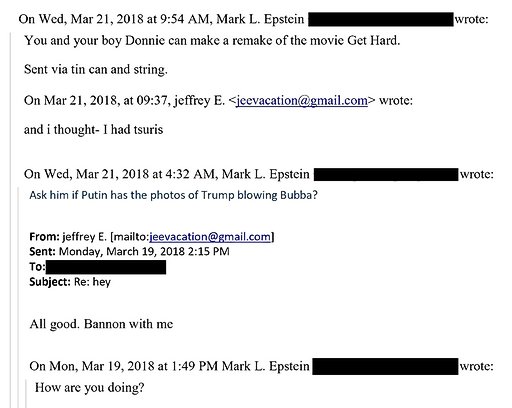

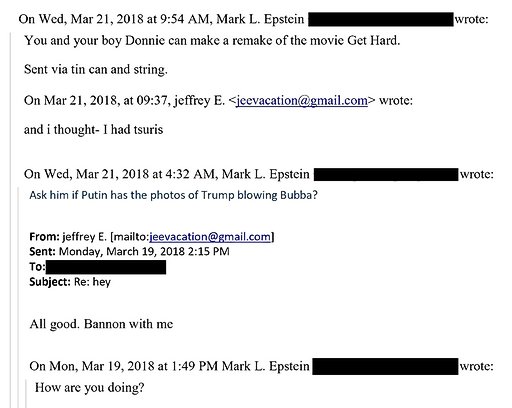

I am genuinely sorry if ErosBlog is the first place where this story reaches you. On Wednesday, the House Oversight Committee released about 20,000 emails pertaining to Jeffry Epstein, and among them was an exchange in which his brother Mark asked him to enquire of Steve Bannon whether Putin “has the photos” of Trump blowing Bubba. And all this time we were waiting for the pee tape:

Who is “Bubba” in these emails? The entire internet wants to believe it’s Bill Clinton, of course, and Bubba is well known to be one of Clinton’s nicknames. However, in fairness it’s a super-common nickname; and Mark Epstein (not a reliable narrator) denied to Newsweek that Clinton was the Bubba in question. So we just don’t know… yet.

The Advocate interviewed Representative Robert Garcia, the top Democrat on the House Oversight Committee, in an attempt to gain additional context. Garcia said the committee lacks sufficient information to accurately interpret the email, adding:

“We’re not sure, actually, what that’s in reference to, obviously. So is it a joke? Is it not? Who’s he talking about? We don’t know. And which is why it’s important for people to know that these emails that we got, they’re from the Epstein estate, right? We got these emails through a subpoena through the estate, and it pales in comparison to what the Department of Justice has to get us as a committee.

There’s a massive cover-up at the White House and the DOJ right now over the files. Those are the documents that we need for us to fill in the blanks and actually put this together.”

But if Putin does indeed have photos of Trump sucking Bubba’s cock, does it even matter who Bubba turns out to be? Those photos would explain an awful lot about Trump’s peculiar subservience to Russian interests over the years.

Similar Sex Blogging:

November 12th, 2025 -- by Bacchus

I don’t think I’ve ever stayed at a hotel fancy enough to offer genuine makeup-removing towels rather than those throw-away circular cotton pads. But if I did? I’m sure my answer would be the same as this guy:

Jessi asks her unidentified off-camera man:

Hey, baby. Um, I just wanna know. I’m very curious. If you had two options, the white towel or the beauty/makeup towel, which one would you go to, to use it as a cumrag?

The beauty one.

That’s what I thought. So you guys, all you men… use this one, that we use to clean our face?

Yeah. That’s why your faces are so good.

Oh, that’s why I have clear skin?

Yep.

Cause I use the cum rag.

That’s right.

That’s disturbing. Thank you.

You’re welcome.

She didn’t even ask him why. From her demeanor, I’m sure she just assumes it’s because men are mischievous perverts. But I’ll offer an additional two practical reasons.

First, that towel in the video looks a lot softer than the typical harsh white terry hand towels of first resort in your average hotel.

And second, jizz dries yellow. A lot of men have been shamed for leaving behind yellow crusties in their laundry whites, whenever they’ve been caught in a circumstance where they don’t have full control over their ejaculatory circumstances or their laundry circumstances either one. Picking the dark colored cumrag is learned behavior for such men. It doesn’t matter that you’ll never see the housekeepers, the behavior is coded deeper than rationality.

Similar Sex Blogging:

|

|